1940 Movie in Which a Millionaire Fall in Love With One of Three Sisters and His Family Disapproved

| Buster Keaton | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Joseph Frank Keaton (1895-10-04)October 4, 1895 Piqua, Kansas, U.South. |

| Died | Feb 1, 1966(1966-02-01) (aged 70) Woodland Hills, Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Resting place | Forest Backyard Memorial Park, Hollywood Hills |

| Occupation |

|

| Years active | 1899–1966 |

| Spouse(s) | Natalie Talmadge (one thousand. 1921; div. 1932) Mae Scriven (m. 1933; div. 1936) Eleanor Keaton (one thousand. 1940) |

| Children | 2 |

| Parent(s) |

|

Joseph Frank "Buster" Keaton (October four, 1895 – February 1, 1966)[1] was an American role player, comedian and filmmaker.[ii] He is best known for his silent films, in which his trademark was physical comedy with a consistently stoic, deadpan expression that earned him the nickname "The Peachy Stone Confront".[3] [4] Critic Roger Ebert wrote of Keaton'south "boggling period from 1920 to 1929" when he "worked without interruption" as having fabricated him "the greatest actor-managing director in the history of the movies".[4] In 1996, Amusement Weekly recognized Keaton as the seventh-greatest film director,[5] and in 1999 the American Pic Plant ranked him every bit the 21st-greatest male star of archetype Hollywood cinema.[6]

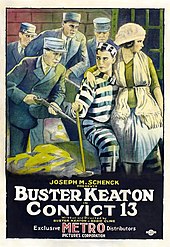

Working with independent producer Joseph One thousand. Schenck, Keaton made a series of successful two-reel comedies in the early 1920s, including One Week (1920), The Playhouse (1921), Cops (1922), and The Electric Business firm (1922). He so moved to feature-length films; several of them, such every bit Sherlock Jr. (1924), The General (1926), and The Cameraman (1928), remain highly regarded.[7] The Full general is widely viewed as his masterpiece: Orson Welles considered it "the greatest comedy ever made...and possibly the greatest film ever fabricated".[8] [ix] [10] [11] His career declined when he signed with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer and lost his artistic independence. His wife divorced him, and he descended into alcoholism. He recovered in the 1940s, remarried, and revived his career as an honored comic performer for the balance of his life, earning an University Honorary Award in 1959.

Career [edit]

Early life in vaudeville [edit]

Keaton was born into a vaudeville family unit in Piqua, Kansas,[12] the small town where his mother, Myra Keaton (née Cutler), was when she went into labor. He was named Joseph to continue a tradition on his father'due south side (he was sixth in a line bearing the name Joseph Keaton)[1] and Frank for his maternal grandfather, who disapproved of his parents' union. His male parent was Joseph Hallie "Joe" Keaton, who owned a traveling show with Harry Houdini called the Mohawk Indian Medicine Company, or the Keaton Houdini Medicine Show Company, which performed on phase and sold patent medicine on the side.[ citation needed ] [13]

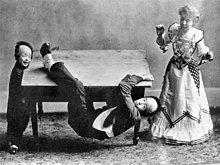

Six-twelvemonth-old Buster and his parents Myra and Joe Keaton, in a publicity photograph for their vaudeville deed

According to a frequently repeated story, which may be counterfeit,[xiv] Keaton caused the nickname Buster at the age of about 18 months. An histrion friend named George Pardey was nowadays one day when the young Keaton took a tumble down a long flight of stairs without injury. After the infant sat up and shook off the experience, Pardey remarked, "He'southward a regular buster!"[15] Subsequently this, Keaton'south father began to use the nickname to refer to the youngster. Keaton retold the anecdote over the years, including in a 1964 interview with the CBC'south Telescope.[sixteen] In Keaton'southward retelling, he was six months old when the incident occurred, and Harry Houdini gave him the nickname.[15]

At the age of three, Keaton began performing with his parents in The 3 Keatons. He first appeared on stage in 1899 in Wilmington, Delaware. The human activity was mainly a comedy sketch. Myra played the saxophone to one side, while Joe and Buster performed center stage. The young Keaton goaded his father by disobeying him, and the elder Keaton responded past throwing him confronting the scenery, into the orchestra pit, or even into the audience. A suitcase handle was sewn into Keaton's clothing to assistance with the constant tossing. The human action evolved as Keaton learned to accept play tricks falls safely; he was rarely injured or bruised on stage. This knockabout mode of comedy led to accusations of child corruption, and occasionally, abort. Withal, Buster was e'er able to show the authorities that he had no bruises or cleaved bones. He was eventually billed equally "The Little Boy Who Can't Be Damaged", and the overall act equally "The Roughest Act That Was Ever in the History of the Stage".[17] Decades later, Keaton said that he was never hurt past his begetter and that the falls and concrete comedy were a affair of proper technical execution. In 1914, he told the Detroit News: "The secret is in landing limp and breaking the autumn with a foot or a manus. Information technology'southward a knack. I started so young that landing right is 2d nature with me. Several times I'd take been killed if I hadn't been able to land similar a cat. Imitators of our act don't final long, because they can't stand the handling."[17]

Keaton said he had and so much fun that he sometimes began laughing as his father threw him across the phase. Noticing that this acquired the audience to laugh less, he adopted his famous deadpan expression when performing.[eighteen]

The act ran up against laws banning child performers in vaudeville. According to one biographer, Keaton was made to go to schoolhouse while performing in New York, but only attended for role of one day.[19] Despite tangles with the police force and a disastrous bout of music halls in the United Kingdom, Keaton was a rising star in the theater. He stated that he learned to read and write belatedly, and was taught by his mother. By the fourth dimension he was 21, his father's alcoholism threatened the reputation of the family act,[17] so Keaton and his female parent, Myra, left for New York, where Buster's career apace moved from vaudeville to film.[20]

Keaton served in the American Expeditionary Forces in France with the United States Army'due south 40th Infantry Partition during World War I. His unit remained intact and was not broken up to provide replacements, every bit happened to another late-arriving divisions. During his time in compatible, he suffered an ear infection that permanently impaired his hearing.[21] [22]

Film [edit]

Silent movie era [edit]

Keaton spent the summers of 1908–1916 "at the 'Actor's Colony' in the Bluffton neighborhood of Muskegon, along with other famous vaudevillians."[23]

In February 1917, he met Roscoe "Fat" Arbuckle at the Talmadge Studios in New York Urban center, where Arbuckle was nether contract to Joseph G. Schenck. Joe Keaton disapproved of films, and Buster also had reservations about the medium. During his starting time meeting with Arbuckle, he was asked to bound in and start acting. Buster was such a natural in his first film, The Butcher Boy, he was hired on the spot. At the end of the day, he asked to borrow ane of the cameras to go a experience for how information technology worked. He took the photographic camera back to his hotel room where he dismantled and reassembled it by morn.[24] Keaton later claimed that he was before long Arbuckle's second director and his entire gag department. He appeared in a full of fourteen Arbuckle shorts, running into 1920. They were popular, and opposite to Keaton'due south later reputation as "The Groovy Stone Confront", he oftentimes smiled and even laughed in them. Keaton and Arbuckle became shut friends, and Keaton was i of few people, along with Charlie Chaplin, to defend Arbuckle's character during accusations that he was responsible for the decease of actress Virginia Rappe. (Arbuckle was eventually acquitted, with an apology from the jury for the ordeal he underwent.[25])

In 1920, The Saphead was released, in which Keaton had his outset starring part in a full-length feature. It was based on a successful play, The New Henrietta, which had already been filmed in one case, under the championship The Lamb, with Douglas Fairbanks playing the lead. Fairbanks recommended Keaton to take the role for the remake five years later, since the pic was to have a comic slant.

PLAY a clip from the beginning of Cops (1922); runtime 00:01:42.

Afterwards Keaton's successful work with Arbuckle, Schenck gave him his own product unit, Buster Keaton Productions. He made a series of two-reel comedies, including I Week (1920), The Playhouse (1921), Cops (1922), and The Electric Firm (1922). Keaton then moved to full-length features.

Keaton's writers included Clyde Bruckman, Joseph Mitchell, and Jean Havez, merely the almost ingenious gags were mostly conceived by Keaton himself. Comedy managing director Leo McCarey, recalling the freewheeling days of making slapstick comedies, said, "All of u.s. tried to steal each other's gagmen. Merely we had no luck with Keaton because he thought upward his all-time gags himself and we couldn't steal him!"[26] The more adventurous ideas called for dangerous stunts, performed by Keaton at great concrete chance. During the railroad water-tank scene in Sherlock Jr., Keaton broke his cervix when a torrent of water fell on him from a water belfry, but he did not realize it until years afterwards. A scene from Steamboat Bill, Jr. required Keaton to stand still on a particular spot. And then, the facade of a two-story building toppled forwards on summit of Keaton. Keaton'due south character emerged unscathed, due to a unmarried open window. The stunt required precision, considering the prop house weighed two tons, and the window only offered a few inches of clearance effectually Keaton's body. The sequence furnished one of the near memorable images of his career.[27]

Bated from Steamboat Bill, Jr. (1928), Keaton'southward virtually indelible feature-length films include Our Hospitality (1923), The Navigator (1924), Sherlock Jr. (1924), Seven Chances (1925), The Cameraman (1928), and The Full general (1926). The General, ready during the American Civil War, combined physical comedy with Keaton's love of trains, including an epic locomotive hunt. Employing picturesque locations, the motion-picture show's storyline reenacted an actual wartime incident. Though it would come to be regarded as Keaton's greatest achievement, the moving-picture show received mixed reviews at the time. It was too dramatic for some filmgoers expecting a lightweight comedy, and reviewers questioned Keaton's judgment in making a comedic motion-picture show virtually the Civil State of war, even while noting information technology had a "few laughs."[28]

It was an expensive misfire, and Keaton was never entrusted with total control over his films again. His distributor, United Artists, insisted on a production manager who monitored expenses and interfered with sure story elements. Keaton endured this treatment for two more characteristic films, and and then exchanged his independent setup for employment at Hollywood's biggest studio, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM). Keaton's loss of independence as a filmmaker coincided with the coming of sound films (although he was interested in making the transition) and mounting personal problems, and his career in the early sound era was hurt every bit a result.[29]

Sound era [edit]

Keaton signed with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer in 1928, a business decision that he would after telephone call the worst of his life. He realized too tardily that the studio organization MGM represented would severely limit his creative input. For instance, the studio refused his request to make his early projection, Spite Marriage, as a sound film and after the studio converted, he was obliged to adhere to dialogue-laden scripts. Nonetheless, MGM did let Keaton some artistic participation on his terminal originally developed/written silent film The Cameraman, 1928, which was his outset project under contract with them, but hired Edward Sedgwick every bit the official director.

Keaton was forced to use a stunt double during some of the more than dangerous scenes, something he had never washed in his heyday, as MGM wanted badly to protect its investment. "Stuntmen don't get laughs," Keaton had said. Some of his most financially successful films for the studio were made during this period. MGM tried teaming the laconic Keaton with the rambunctious Jimmy Durante in a series of films, The Passionate Plumber, Speak Easily, and What! No Beer? [30] The latter would exist Keaton's terminal starring feature in his home country. The films proved pop. (Thirty years later, both Keaton and Durante had cameo roles in Information technology's a Mad Mad Mad Mad Globe, albeit not in the aforementioned scenes.)

In the kickoff Keaton pictures with sound, he and his fellow actors would shoot each scene iii times: in one case in English, one time in Spanish, and once in either French or German. The actors would phonetically memorize the strange-linguistic communication scripts a few lines at a time and shoot immediately subsequently. This is discussed in the TCM documentary Buster Keaton: So Funny it Hurt, with Keaton complaining about having to shoot lousy films not simply in one case, but three times.

Keaton was and then demoralized during the production of 1933's What! No Beer? that MGM fired him after the filming was complete, despite the moving picture being a resounding striking. In 1934, Keaton accepted an offer to make an independent film in Paris, Le Roi des Champs-Élysées. During this menses, he made some other film in England, The Invader (released in the The states equally An Onetime Spanish Custom in 1936).[30]

Educational Pictures [edit]

Upon Keaton's return to Hollywood in 1934, he made a screen comeback in two-reel comedies for Educational Pictures. Well-nigh of these sixteen films are simple visual comedies, with many of the gags supplied by Keaton himself, often recycling ideas from his family vaudeville human activity and his earlier films.[31] The loftier point in the Educational series is Grand Slam Opera (1936), featuring Buster in his own screenplay as an amateur-hour contestant.

Gag writer [edit]

When the Educational series lapsed in 1937, Keaton returned to MGM equally a gag author, supplying material for the final three Marx Brothers MGM films At the Circus (1939), Go Due west (1940), and The Big Store (1941); these were not as artistically successful as the Marxes' previous MGM features.

Columbia Pictures [edit]

In 1939, Columbia Pictures hired Keaton to star in 10 two-reel comedies; the series ran for two years, and comprise his last series as a starring comedian. The managing director was usually Jules White, whose emphasis on slapstick and farce made well-nigh of these films resemble White's famous Three Stooges shorts. Keaton'southward personal favorite was the series's debut, Pest from the W, a shorter, tighter remake of Keaton's footling-viewed 1934 characteristic The Invader; it was directed non by White just past Del Lord, a veteran director for Mack Sennett. Moviegoers and exhibitors welcomed Keaton'due south Columbia comedies, proving that the comedian had not lost his appeal. Nevertheless, managing director White's insistence on edgeless, violent gags resulted in the Columbia shorts being the least inventive comedies he made. The final entry was She'south Oil Mine (1941), a two-reel reworking of Keaton's 1932 feature The Passionate Plumber. Columbia and White wanted to sign Keaton for more than shorts but the comedian declined, resolving that he would never again "make some other crummy two-reeler."[32]

1940s and feature films [edit]

Keaton'south personal life had stabilized with his 1940 marriage to MGM dancer Eleanor Norris, and now he was taking life a little easier, abandoning Columbia for the less strenuous field of characteristic films. Resuming his daily chore as an MGM gag writer, he provided cloth for Crimson Skelton[33] and gave help and communication to Lucille Ball.[34]

Keaton accepted various graphic symbol roles in both "A" and "B" features. He fabricated his terminal starring feature El Moderno Barba Azul (1946) in Mexico; the movie was a low-budget production, and it may not have been seen in the U.s.a. until its release on VHS in the 1980s, nether the title Boom in the Moon. The motion picture has a largely negative reputation, with renowned flick historian Kevin Brownlow calling it the worst movie ever made.[35]

Critics rediscovered Keaton in 1949 and producers occasionally hired him for bigger "prestige" pictures. He had cameos in such films equally In the Skilful Old Summertime (1949), Sunset Boulevard (1950), and Around the World in 80 Days (1956). In In the Skillful One-time Summertime, Keaton personally directed the stars Judy Garland and Van Johnson in their first scene together, where they bump into each other on the street. Keaton invented comedy $.25 where Johnson keeps trying to apologize to a seething Garland, but winds up messing upwards her hairdo and tearing her clothes.

Keaton also appeared in a comedy routine about two inept stage musicians in Charlie Chaplin's Limelight (released in 1952), recalling the vaudeville of The Playhouse. With the exception of Seeing Stars, a minor publicity motion picture produced in 1922, Limelight was the only fourth dimension in which the ii would ever announced together on film.

Television and rediscovery [edit]

In 1949, comedian Ed Wynn invited Keaton to appear on his CBS Television one-act-diverseness bear witness, The Ed Wynn Show, which was televised live on the West Coast. Kinescopes were made for distribution of the programs to other parts of the country, since at that place was no transcontinental coaxial cablevision until September 1951. Reaction was potent enough for a local Los Angeles station to offering Keaton his own testify, also broadcast live, in 1950.

Life with Buster Keaton (1951) was an attempt to recreate the first series on film, allowing the program to be broadcast nationwide. The series benefited from a company of veteran actors, including Marcia Mae Jones as the ingenue, Iris Adrian, Dick Wessel, Fuzzy Knight, Dub Taylor, Philip Van Zandt, and his silent-era contemporaries Harold Goodwin, Hank Isle of mann, and stuntman Harvey Parry. Buster Keaton's married woman Eleanor also was seen in the series (notably as Juliet to Buster's Romeo in a little-theater vignette). The theatrical feature film The Misadventures of Buster Keaton was fashioned from the series. Keaton said that he canceled the filmed series himself, because he was unable to create enough fresh fabric to produce a new show each week.

Keaton's periodic television appearances during the 1950s and 1960s helped to revive interest in his silent films. He appeared in the early television series Faye Emerson'south Wonderful Town. Whenever a TV prove wanted to simulate silent-movie one-act, Buster Keaton answered the call and guested in such successful series as The Ken Murray Testify, Yous Asked for It, and The Garry Moore Evidence, and The Ed Sullivan Show. Well into his fifties, Keaton successfully recreated his erstwhile routines, including one stunt in which he propped one foot onto a table, and so swung the 2d foot upward next to information technology and held the awkward position in midair for a moment before crashing to the stage floor. Garry Moore recalled, "I asked (Keaton) how he did all those falls, and he said, 'I'll show you.' He opened his jacket and he was all bruised. So that'southward how he did it—it hurt—just you lot had to care enough not to care."

Silent films revived [edit]

In 1954, Buster and Eleanor Keaton met film programmer Raymond Rohauer, with whom they developed a business partnership to re-release his films. Actor James Mason had bought the Keatons' house and found numerous cans of films, amongst which was Keaton'south long-lost classic The Boat.[36] Keaton had prints of the features Iii Ages, Sherlock Jr., Steamboat Bill, Jr., and Higher (missing 1 reel), and the shorts "The Boat" and "My Married woman'due south Relations", which Keaton and Rohauer and so transferred to Cellulose acetate film from deteriorating nitrate pic stock.[37]

From 1950 through 1964, Keaton made around 70 guest appearances on television receiver variety shows, including those of Ed Sullivan and Garry Moore.[38] Keaton besides found steady work every bit an actor in Tv set commercials for Colgate, Alka-Seltzer, U.Due south. Steel, 7-Up, RCA Victor, Phillips 66, Milky way, Ford Motors, Minute Rub, and Budweiser, among others.[39] In a series of silent television commercials for Simon Pure Beer made in 1962 by Jim Mohr in Buffalo, New York, Keaton revisited some of the gags from his silent moving-picture show days.[40]

On April iii, 1957, Keaton was surprised past Ralph Edwards for the weekly NBC plan This Is Your Life. The plan also promoted the release of the biographical picture The Buster Keaton Story with Donald O'Connor.[41] In December 1958, Keaton was a invitee star in the episode "A Very Merry Christmas" of The Donna Reed Evidence on ABC. He returned to the plan in 1965 in the episode "At present Yous Encounter It, Now Yous Don't".[42] In Baronial 1960, Keaton played mute King Sextimus the Silent in the national touring company of the Broadway musical Once Upon A Mattress.[43] In 1960, he returned to MGM for the final fourth dimension, playing a lion tamer in a 1960 accommodation of Mark Twain's The Adventures of Blueberry Finn. Much of the movie was shot on location on the Sacramento River, which doubled for the Mississippi River setting of Twain'south book.[44] In 1961, he starred in The Twilight Zone episode "Once Upon a Time", which included both silent and sound sequences. He worked with comedian Ernie Kovacs on a television pilot tentatively titled "Medicine Man," shooting scenes for it on January 12, 1962—the day before Kovacs died in a automobile crash. "Medicine Man" was completed but not aired.[45]

Meanwhile, Keaton's big-screen career continued. He had a cameo as Jimmy, actualization near the end of the film It'south a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World (1963). Jimmy assists Spencer Tracy's character, Captain C. Thou. Culpepper, by readying Culpepper's ultimately-unused boat for his abortive escape. (The restored version of that moving-picture show, released in 2013, contains a scene where Jimmy and Culpeper talk on the phone. Lost after the comedy ballsy'southward "roadshow" exhibition, the sound of that scene was discovered and combined with yet pictures to recreate the scene.)

Keaton starred in four films for American International Pictures: 1964'southward Pajama Party and 1965's Beach Coating Bingo, How to Stuff a Wild Bikini, and Sergeant Deadhead. Director William Asher recalled:

I always loved Buster Keaton.… He would bring me bits and routines. He'd say, "How about this?" and it would just exist this wonderful, inventive stuff.[46]

In 1965, Keaton starred in the brusque film The Railrodder for the National Movie Board of Canada. He traveled from one end of Canada to the other on a motorized handcar, wearing his traditional pork pie lid and performing gags similar to those in films that he made fifty years before. The film is also notable for existence his last silent screen functioning.[47] He played the central part in Samuel Beckett's Film (1965), directed past Alan Schneider. Also in 1965, he traveled to Italy to play a role in Due Marines east un Generale, co-starring Franco Franchi and Ciccio Ingrassia.

In 1965 he appeared on the CBS television special A Salute to Stan Laurel, a tribute to the comedian and friend of Keaton who had died earlier that year.

Keaton'due south concluding commercial pic advent was in A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum (1966), which was filmed in Spain in September–November 1965. He amazed the bandage and crew by doing many of his own stunts, although Thames Television said that his increasingly ill health did force the use of a stunt double for some scenes. His final appearance on pic was in The Scribe, a 1966 safe picture show produced in Toronto by the Construction Condom Associations of Ontario: he died before long after completing it.[48]

Style and themes [edit]

Apply of parody [edit]

Keaton started experimenting with parody during his vaudeville years, where most ofttimes his performances involved impressions and burlesques of other performers' acts. Most of these parodies targeted acts with which Keaton had shared the neb.[49] When Keaton transposed his experience in vaudeville to picture, in many works he parodied melodramas.[49] Other favorite targets were cinematic plots, structures and devices.[50]

One of his most biting parodies is The Frozen North (1922), a satirical take on William S. Hart'southward Western melodramas, like Hell'due south Hinges (1916) and The Narrow Trail (1917). Keaton parodied the tired formula of the melodramatic transformation from bad guy to good guy, which Hart's characters went through, known as "the good badman".[51] He wears a small version of Hart's entrada lid from the Spanish–American State of war and a half-dozen-shooter on each thigh, and during the scene in which he shoots the neighbor and her husband, he reacts with thick glycerin tears, a trademark of Hart's.[52] Audiences of the 1920s recognized the parody and thought the film hysterically funny. Even so, Hart himself was not tickled by Keaton's antics, especially the crying scene, and did not speak to Buster for two years after he had seen the film.[53] The film's opening intertitles requite it its mock-serious tone, and are taken from "The Shooting of Dan McGrew" past Robert W. Service.[53]

In The Playhouse (1921), he parodied his contemporary Thomas H. Ince, Hart's producer, who indulged in over-crediting himself in his film productions. The short also featured the impression of a performing monkey which was likely derived from a co-biller'south act (called Peter the Groovy).[49] Iii Ages (1923), his start feature-length flick, is a parody of D. Due west. Griffith's Intolerance (1916), from which it replicates the three inter-cut shorts structure.[49] Three Ages also featured parodies of Bible stories, like those of Samson and Daniel.[51] Keaton directed the film, along with Edward F. Cline. By this time, Keaton had further developed his singled-out signature way that consisted of lucidity and precision along with acrobatics of ballistic precision and kineticism.[54] [55] Critic and Film Historian Imogen Sara Smith stated almost Keaton'south fashion:

"the coolness and subtlety of his way [is] very cinematic in terms of recognising that the camera tin pick upwards very, very small effects".[54]

Body linguistic communication [edit]

| External sound | |

|---|---|

| |

Picture critic David Thomson later described Keaton's style of comedy: "Buster apparently is a man inclined towards a belief in nothing only mathematics and applesauce ... like a number that has ever been searching for the right equation. Wait at his face—as beautiful but as inhuman equally a butterfly—and you see that utter failure to identify sentiment."[56] Gilberto Perez commented on "Keaton's genius equally an actor to keep a confront so most deadpan and yet render it, past subtle inflections, so vividly expressive of inner life. His big, deep eyes are the most eloquent feature; with merely a stare, he can convey a wide range of emotions, from longing to mistrust, from puzzlement to sorrow."[57] Critic Anthony Lane also noted Keaton'southward trunk language:

The traditional Buster stance requires that he remain ethical, full of backbone, looking alee... [in The General] he clambers onto the roof of his locomotive and leans gently forward to scan the terrain, with the breeze in his hair and adventure zipping toward him around the next curve. It is the angle that you retrieve: the figure perfectly straight but tilted forward, similar the Spirit of Ecstasy on the hood of a Rolls-Royce... [in The Three Ages], he drives a depression-grade automobile over a bump in the road, and the automobile just crumbles beneath him. Rerun it on video, and you tin can see Buster riding the collapse similar a surfer, hanging onto the steering wheel, coming beautifully to residuum as the wave of wreckage breaks.[58]

Picture historian Jeffrey Vance wrote:

Buster Keaton'south comedy endures non merely because he had a face that belongs on Mountain Rushmore, at in one case hauntingly immovable and classically American, but because that confront was attached to one of the about gifted actors and directors who e'er graced the screen. Evolved from the knockabout upbringing of the vaudeville stage, Keaton's one-act is a cyclone of hilarious, technically precise, adroitly executed, and surprising gags, very often gear up against a backdrop of visually stunning set pieces and locations—all this masked backside his unflinching, stoic veneer.[59]

Keaton has inspired full bookish study.[threescore]

Personal life [edit]

On May 31, 1921, Keaton married Natalie Talmadge, his leading lady in Our Hospitality, and the sister of actresses Norma Talmadge (married to his concern partner Joseph Yard. Schenck at the time) and Constance Talmadge, at Norma's home in Bayside, Queens. They had ii sons: Joseph, chosen James[61] (June 2, 1922 – February 14, 2007),[62] and Robert (February 3, 1924 – July 19, 2009).[63]

After Robert'due south nativity, the marriage began to suffer.[14] Talmadge decided not to accept any more than children, banishing Keaton to a separate bedroom; he dated actresses Dorothy Sebastian, and Kathleen Central during this period.[64] Natalie's extravagance was another factor, spending up to a third of her husband's earnings. No penny-pincher himself, Keaton hired Gene Verge Sr. in 1926 to build a 10,000-foursquare-foot (930 m2) manor in Beverly Hills for $300,000, which was later endemic by James Mason and Cary Grant.[65] After attempts at reconciliation, she divorced him in 1932, and inverse the boys' surname to "Talmadge".[66] On July 1, 1942, the at present-18 year erstwhile Robert and the now-20 year old Joseph fabricated the proper noun change permanent after their female parent won a court petition.[67]

With the failure of his marriage and the loss of his independence as a filmmaker, Keaton descended into alcoholism.[fourteen] He was briefly institutionalized, according to the Turner Classic Movies documentary Then Funny it Hurt. He escaped a straitjacket with tricks learned from Harry Houdini. In 1933, he married his nurse Mae Scriven during an alcoholic binge well-nigh which he after claimed to remember nothing. Scriven claimed that she didn't know Keaton's real first name until afterwards the marriage. She filed for divorce in 1935 after finding him with Leah Clampitt Sewell, the wife of millionaire Barton Sewell,[68] in a hotel in Santa Barbara. They divorced in 1936[69] at great financial toll to Keaton.[70] After undergoing disfavor therapy, he stopped drinking for five years.[71]

On May 29, 1940, Keaton married Eleanor Norris, who was 23 years his junior. She has been credited with salvaging his life and career.[72] The union lasted until his death. Between 1947 and 1954, the couple appeared regularly in the Cirque Medrano in Paris every bit a double human action. She came to know his routines and so well that she often participated in them on television revivals.

Expiry [edit]

Keaton died of lung cancer on Feb one, 1966, aged seventy, in Woodland Hills, California.[73] Despite being diagnosed with cancer in January 1966, he was never told he was terminally ill. Keaton thought that he was recovering from a severe case of bronchitis. Confined to a infirmary during his final days, Keaton was restless and paced the room incessantly, desiring to return home. In a British tv documentary nigh his career, his widow Eleanor told producers from Thames Television that Keaton was up out of bed and moving around, and even played cards with friends who came to visit the 24-hour interval before he died.[74] He was buried at Forest Lawn Memorial Park Cemetery in Hollywood Hills, California.[ citation needed ]

Influence and legacy [edit]

Keaton was presented with a 1959 Academy Honorary Award at the 32nd Academy Awards, held in April 1960.[75] Keaton has two stars on the Hollywood Walk of Fame: 6619 Hollywood Boulevard (for motion pictures); and 6225 Hollywood Boulevard (for television).

6 of his films take been included in the National Film Registry, making him ane of the about honored filmmakers on that prestigious list: One Week (1920), Cops (1922), Sherlock Jr. (1924), The General (1926), Steamboat Bill Jr., and The Cameraman (both 1928)[76]

A 1957 film biography, The Buster Keaton Story, starring Donald O'Connor as Keaton was released.[33] The screenplay, by Sidney Sheldon, who also directed the film, was loosely based on Keaton's life just contained many factual errors and merged his 3 wives into one grapheme.[77] A 1987 documentary, Buster Keaton: A Hard Act to Follow, directed by Kevin Brownlow and David Gill, won 2 Emmy Awards.[78]

The International Buster Keaton Club was founded on October iv, 1992: Keaton'south altogether. Dedicated to bringing greater public attention to Keaton's life and piece of work, the membership includes many individuals from the tv and motion picture industry: actors, producers, authors, artists, graphic novelists, musicians, and designers, likewise as those who simply admire the magic of Buster Keaton. The Society'southward nickname, the "Damfinos," draws its proper name from a gunkhole in Keaton'southward 1921 one-act, The Boat.

In 1994, caricaturist Al Hirschfeld penned a series of silent film stars for the United states Postal service Part, including Rudolph Valentino and Keaton.[79] Hirschfeld said that modern film stars were more than difficult to describe, that silent pic comedians such as Laurel and Hardy and Keaton "looked like their caricatures".[80]

In his essay Moving-picture show-arte, moving-picture show-antiartístico, artist Salvador Dalí alleged the works of Keaton to be prime examples of "anti-artistic" filmmaking, calling them "pure poetry". In 1925, Dalí produced a collage titled The Marriage of Buster Keaton featuring an image of the comedian in a seated pose, staring straight ahead with his trademark boater hat resting in his lap.[81]

Film critic Roger Ebert stated, "The greatest of the silent clowns is Buster Keaton, not but considering of what he did, but because of how he did it. Harold Lloyd made us express mirth as much, Charlie Chaplin moved us more deeply, just no one had more courage than Buster."[82]

In his presentation for The General, filmmaker Orson Welles hailed Buster Keaton every bit "the greatest of all the clowns in the history of the cinema... a supreme artist, and I think one of the most cute people who was ever photographed".

Filmmaker Mel Brooks has credited Buster Keaton equally a major influence, saying: "I owe (Buster) a lot on two levels: 1 for beingness such a great teacher for me as a filmmaker myself, and the other just as a human being watching this gifted person doing these amazing things. He made me believe in make-believe." He also admitted to borrowing the idea of the irresolute room scene in The Cameraman for his own film Silent Movie.[83]

Role player and stunt performer Johnny Knoxville cites Keaton as an inspiration when coming upwardly with ideas for Jackass projects. He re-enacted a famous Keaton stunt for the finale of Jackass Number Two.[84]

Comedian Richard Lewis stated that Keaton was his prime inspiration, and spoke of having a shut friendship with Keaton'due south widow Eleanor. Lewis was particularly moved by the fact that Eleanor said his eyes looked like Keaton'southward.[85]

In 2012, Kino Lorber released The Ultimate Buster Keaton Collection, a fourteen-disc Blu-ray box set of Keaton'due south work, including 11 of his feature films.[86]

On June 16, 2018, the International Buster Keaton Lodge laid a four-foot plaque in honor of both Keaton and Charles Chaplin on the corner of the shared block (1021 Lillian Ave) where each had fabricated many of their silent comedies in Hollywood.[87] In honor of the event, the City of Los Angeles declared the date "Buster Keaton Day."[88]

In 2018 filmmaker Peter Bogdanovich released The Bully Buster: A Celebration, a documentary most Keaton'south life, career, and legacy.

In 2022, critic Dana Stevens published a cultural history of Keaton'south life and piece of work entitled Camera Human: Buster Keaton, the Dawn of Cinema, and the Invention of the Twentieth Century.

In 2022 information technology was reported by Deadline that James Mangold will direct a biopic on Keaton.[89] [90]

Pork pie hats [edit]

Keaton designed and modified his own pork pie hats during his career. In 1964, he told an interviewer that in making "this particular pork pie", he "started with a good Stetson and cut it down", stiffening the brim with sugar water.[91] The hats were ofttimes destroyed during Keaton's wild film antics; some were given away as gifts and some were snatched past souvenir hunters. Keaton said he was lucky if he used only six hats in making a picture. Keaton estimated that he and his wife Eleanor made thousands of hats during his career. Keaton observed that during his silent flow, such a hat cost him effectually ii dollars (~$27-33 in 2022 dollars); at the time of his interview, he said, they toll most $13 (~$116 in 2022 dollars).[91]

References [edit]

- ^ a b Meade, Marion (1997). Buster Keaton: Cut to the Chase. Da Capo. p. 16. ISBN0-306-80802-1.

- ^ Obituary Multifariousness, February ii, 1966, page 63.

- ^ Barber, Nicholas (January 8, 2014). "Deadpan but alive to the future: Buster Keaton the revolutionary". The Independent . Retrieved Nov 3, 2015.

- ^ a b Ebert, Roger (Nov x, 2002). "The Films of Buster Keaton". Archived from the original on November 3, 2015. Retrieved January 28, 2016.

- ^ "The 50 Greatest Directors and Their 100 Best Movies". Entertainment Weekly. April 19, 1996. p. two. Archived from the original on June 26, 2015. Retrieved January 28, 2016.

- ^ "AFI Recognizes the 50 Greatest American Screen Legends" (Press release). American Film Constitute. June 16, 1999. Archived from the original on January thirteen, 2013. Retrieved August 31, 2013.

- ^ "Buster Keaton's Acclaimed Films". They Shoot Pictures, Don't They. Retrieved September 29, 2016.

- ^ "Sight & Sound Critics' Poll (2002): Pinnacle Films of All Time". Sight & Audio via Mubi.com. Archived from the original on January 29, 2016. Retrieved January 29, 2016.

- ^ "Votes for The General (1924)". British Film Institute. Retrieved September 29, 2016.

- ^ Andrew, Geoff (January 23, 2014). "The General: the greatest comedy of all time?". Sight & Sound. Archived from the original on September 6, 2015. Retrieved January 28, 2016.

- ^ Orson Welles interview, from the Kino November 10, 2009 Blu-Ray edition of The Full general

- ^ Stokes, Keith (ed.). "Buster Keaton Museum". KansasTravel.org. Archived from the original on Jan 16, 2016. Retrieved February 17, 2010.

- ^ "County Correspondence". The Butler County Democrat, El Dorado, Kansas. March xix, 1896. p. 8. Retrieved November xi, 2019.

- ^ a b c McGee, Scott. "Buster Keaton: Sundays in October". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved October nineteen, 2017. Note: Source misspells Keaton's frequent appellation as "Great Stoneface".

- ^ a b Meade, Marion (2014). Buster Keaton: Cut to the Chase: A Biography. Open Road Media. p. 19. ISBN 1497602319.

- ^ Telescope: Deadpan: An Interview with Buster Keaton, 1964 interview of Buster and Eleanor Keaton by Fletcher Markle for the CBC.

- ^ a b c "Part I: A Vaudeville Childhood". International Buster Keaton Social club. Archived from the original on Jan viii, 2015. Retrieved February 17, 2010.

- ^ "Buster Keaton". Archive.sensesofcinema.com. Feb ane, 1966. Archived from the original on February two, 2010. Retrieved February 17, 2010.

- ^ Biography: Part 1. www.busterkeaton.org. Retrieved August 26, 2019.

- ^ "Part II:The Flickers". International Buster Keaton Guild. Oct 13, 1924. Archived from the original on March iii, 2015. Retrieved February 17, 2010.

- ^ Martha R. Jett. "My Career at the Rear / Buster Keaton in World War I". worldwar1.com.

- ^ Primary Sergeant Jim Ober. "Buster Keaton: Comedian, Soldier". California Country Military Museum.

- ^ "Muskegon: Buster Keaton documentary to focus on early life in Muskegon". MLive. January 19, 2019. Retrieved March 17, 2021.

- ^ Prikryl, Jana (July 9, 2011), "The Genius of Buster", The New York Review of Books, 58 (10): xxx–33.

- ^ Yallop, David (1976). The Day the Laughter Stopped. New York: St. Martin'southward Press. ISBN 978-0-312-18410-0

- ^ Maltin, Leonard, The Bully Moving picture Comedians, Bell Publishing, 1978

- ^ "Reviews : The Full general/Steamboat Bill Jr". The DVD Journal. Retrieved Feb 17, 2010.

- ^ "Moving Pictures: Buster Keaton's 'Full general' Pulls In To PFA. Category: Arts & Entertainment from The Berkeley Daily Planet – Friday November 10, 2006". Berkeleydaily.org. Retrieved February 17, 2010.

- ^ "Buster-Keaton.com". Buster-Keaton.com. Archived from the original on March i, 2010. Retrieved Feb 17, 2010.

- ^ a b Everson, William 1000. American Silent Film. New York: Oxford Academy Press, 1978. p. 274-5.

- ^ Gill, David, Brownlow, Kevin (1987). Buster Keaton: A Hard Act to Follow. Thames Television. pp. Episode three.

- ^ Okuda, Ted; Watz, Edward (1986). The Columbia Comedy Shorts . McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers. p. 139. ISBN0-89950-181-8.

- ^ a b Knopf, Robert The Theater and Cinema of Buster Keaton By p.34

- ^ Kathleen Brady (May 31, 2014). "Lucille The Life of Lucille Ball – Kathleen Brady". kathleenbrady.net.

- ^ Motion picture Threat review Archived January 25, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "The Business firm Next Door: 5 for the Day: James Mason". www.slantmagazine.com. August 24, 2009. Retrieved July 15, 2014.

- ^ Lovece, Frank (June 1987). "Where's Buster? Despite Renewed Involvement, Only a Handful of Buster Keaton'southward Archetype Comedies Are on Tape". Video. Archived from the original on October 7, 2013. Retrieved August 31, 2013.

- ^ Blesh 1967, p. 366.

- ^ Blesh 1967, p. 367.

- ^ "Buster Keaton For Simon Pure Beer – Brookston Beer Message". Brookston Beer Message. October 4, 2015. Retrieved October 11, 2016.

- ^ "Series Details". Cinema.ucla.edu. Retrieved February 17, 2010.

- ^ ""The Donna Reed Show" A Very Merry Christmas (1958)". United states.imdb.com. Retrieved February 17, 2010.

- ^ Meade, Marion (1997). Buster Keaton: Cut to the Chase. Da Capo. p. 284. ISBN0-306-80802-1.

- ^ Crowther, Bosley (August 4, 1960). "The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1960)". The New York Times.

- ^ Spiro, J. D. (February 8, 1962). "Ernie Kovacs' Last Interview". The Milwaukee Journal . Retrieved October 16, 2010.

- ^ Lovece, Frank (February 1987). "Beach Blanket Buster". Video. Archived from the original on Oct thirteen, 2013. Retrieved Baronial 31, 2013.

- ^ "Buster Keaton Rides Again: Render of 'The Keen Stone Face'". DangerousMinds. August 27, 2013.

- ^ Buster Keaton: A Hard Human activity to Follow, Chap. 3, Thames Tv, 1987

- ^ a b c d Knopf, Robert. The Theater and Cinema of Buster Keaton. p. 27.

- ^ Mast, Gerald (1979). The Comic Heed: Comedy and the Movies. p. 135.

- ^ a b Balducci, Anthony (2011). The Funny Parts: A History of Film Comedy Routines and Gags. p. 231.

- ^ Gehring, Wes D. (1990). Laurel & Hardy. ISBN9780313251726.

- ^ a b Keaton, Eleanor; Vance, Jeffrey (2001). Buster Keaton Remembered. H.Northward. Abrams. p. 95.

- ^ a b Davis, Nicole (January 23, 2022). "Why Buster Keaton is today's almost influential actor". BBC Civilization . Retrieved February 28, 2022.

- ^ Stevens, D (January 25, 2022). Camera Human being: Buster Keaton, the Dawn of Cinema, and the Invention of the Twentieth Century. United States: Atria Books. p. 189. ISBN9781501134197.

- ^ Thomson, David, Accept you Seen...?, Alfred A. Knopf Publishing, 2008, p. 767.

- ^ Perez Gilberto 'The Material Ghost—On Keaton and Chaplin' 1998

- ^ Lane, Anthony, Nobody's Perfect, Knopf Publishing, 2002, pgs. 560–561

- ^ Vance, Jeffrey. "Introduction." Keaton, Eleanor and Jeffrey Vance. Buster Keaton Remembered. Harry N. Abrams, 2001, pg. 33. ISBN 0-8109-4227-5

- ^ Trahair, Lisa (October 27, 2004). "The Narrative-Machine: Buster Keaton'south Cinematic One-act, Deleuze's Recursion Function and the Operational Aesthetic". Retrieved October 3, 2019.

- ^ Smith, Imogen Sara (2008). Buster Keaton: The Persistence of Comedy. Gambit Publishing. p. 140. ISBN 0967591740. Retrieved Oct xx, 2019.

- ^ James Talmadge at the Usa Social Security Death Index via FamilySearch.org. Retrieved on December 7, 2015. "Fastened to: Joseph Talmadge Keaton 1922–2007"

- ^ Robert Talmadge at the United states of america Social Security Expiry Index via FamilySearch.org. Retrieved on December seven, 2015

- ^ McPherson, Edward (2007). Buster Keaton: Tempest in a Flat Hat. Newmarket Press. ISBN978-1557046642.

- ^ "The City of Beverly Hills: Historic Resources Inventory (1985–1986)" (PDF) . Retrieved October three, 2019.

- ^ Cox, Melissa Talmadge, in Bible, Karie (May half dozen, 2004). "Interviews: Melissa Talmadge Cox (Buster Keaton's Granddaughter)". Archived from the original on Dec 8, 2015. Retrieved Dec 7, 2015.

My Dad was christened Joseph Talmadge Keaton. When my grandparents divorced, my grandmother took her maiden name back and his name his legally became Talmadge.

- ^ "Keaton Sons Change Names to Talmadge" ladailymirror.com (June thirty, 2012); retrieved October 26, 2021

- ^ "Buster Keaton's Second Wife Sues Him for Divorce". Reading Eagle. July 18, 1935. Retrieved May 7, 2012.

- ^ "Keaton Divorce Made Final". The New York Times. October 28, 1936. p. 31. Retrieved September 29, 2019.

- ^ Dardis, Tom (1979). Keaton: The Human being Who Wouldn't Prevarication Down. Andre Deutsch. ISBN978-0233971377.

- ^ Pull a fast one on, Charlie. "Buster Keaton's Cure | Charlie Trick". cabinetmagazine.org . Retrieved Jan 14, 2021.

- ^ Vance, Jeffrey. "Introduction." Keaton, Eleanor and Jeffrey Vance. Buster Keaton Remembered. Harry N. Abrams, 2001, pg. 29. ISBN 0-8109-4227-v

- ^ "Buster Keaton, seventy, Dies on Coast. Poker-Faced Comedian of Films". The New York Times. February 2, 1966. Retrieved July 4, 2008.

Buster Keaton, the poker-faced comic whose studies in exquisite frustration amused two generations of film audiences, died of lung cancer today at his home in suburban Woodland Hills.

- ^ Turner Archetype Movies.

- ^ "Buster Keaton". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved Jan 21, 2018.

- ^ "Services 2 — The Damfinos". Busterkeaton.org. October 3, 2020. Retrieved Feb 26, 2022.

- ^ Erickson, Hal (2009). "The Buster Keaton Story". Movies & Television Dept. The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 27, 2009. Retrieved Feb 17, 2010.

- ^ "Buster Keaton: A Hard Act to Follow (American Masters)". Emmys.com. Archived from the original on March 13, 2018. Retrieved June 22, 2014.

- ^ Associated Press, Polly Anderson, Jan twenty, 2003. "Famed Caricaturist Al Hirschfeld Dies".

- ^ Leopold, David. Hirschfeld's Hollywood, Academy of Motion Movie Arts and Sciences, p. twenty.

- ^ Elder, R. Bruce (2015). Dada, Surrealism, and the Cinematic Issue. Wilfrid Laurier Univ. Press. p. 623. ISBN 1554586410.

- ^ Ebert, Roger, and Mary Corliss (2005). The Nifty Movies Ii. New York: Broadway Books. p. 93. ISBN 9780307485663.

- ^ "Mel Brooks on Buster Keaton--The Lybarger Links Interview". www.tipjar.com.

- ^ Ressner, Jeffrey (September 29, 2006). "The Foreign Behavior of Johnny Knoxville". Time. Archived from the original on October 19, 2016. Retrieved May 25, 2018.

- ^ TCM voice-over, October 2011, "Buster Keaton Calendar month".

- ^ Rafferty, Terrence (January 2013). "DVD Classics: Laugh Out Loud". DGA Quarterly. Winter. Retrieved January 12, 2013.

- ^ Bell, Nathaniel (June 12, 2018). "Keaton Weekend in L.A. Celebrates the Great Silent Comedian".

- ^ "Urban center of Los Angeles to declare June xvi, 2018 "Buster Keaton Day"". May 22, 2018. Archived from the original on August nineteen, 2018. Retrieved December thirteen, 2018.

- ^ Kroll, Justin; Kroll, Justin (February 23, 2022). "James Mangold To Straight Buster Keaton Biopic For 20th Century". Deadline . Retrieved February 23, 2022.

- ^ "James Mangold To Direct Buster Keaton Biopic For 20th Century Studios". Empire . Retrieved February 23, 2022.

- ^ a b "How To Make A Porkpie Hat. Buster Keaton, interviewed in 1964 at the Movieland Wax Museum by Henry Gris". Busterkeaton.com. Archived from the original on February 3, 1998. Retrieved Feb 17, 2010.

Further reading [edit]

- Agee, James, "Comedy's Greatest Era" from Life (September five, 1949), reprinted in Agee on Film (1958), McDowell, Obolensky (2000), Modernistic Library

- Anobile, Richard J. (ed.) (1976), The Best of Buster: Archetype Comedy Scenes Direct from the Films of Buster Keaton. Crown Books.

- Benayoun, Robert, The Look of Buster Keaton (1983) St. Martin'southward Printing

- Bengtson, John (1999), Silent Echoes: Discovering Early Hollywood Through the Films of Buster Keaton, Santa Monica Press.

- Blesh, Rudi (1967). Keaton. Secker & Warburg – via Cyberspace Annal.

- Brighton, Catherine (2008), Keep Your Eye on the Kid: The Early Years of Buster Keaton, Roaring Brook Press. An illustrated children's book about Keaton's career.

- Brownlow, Kevin, "Buster Keaton" from The Parade'southward Gone Past. Alfred A. Knopf (1968), Academy of California Press (1976)

- Byron, Stuart and Weis, Elizabeth (eds.) (1977), The National Club of Moving-picture show Critics on Flick Comedy, Grossman/Viking

- Carroll, Noel (2009), Comedy Incarnate: Buster Keaton, Physical Humor, and Bodily Coping, Wiley-Blackwell

- Dardis, Tom, Keaton: The Man Who Wouldn't Prevarication Down, Scribners (1979), Limelight Editions (2004)

- Robinson, David (1969), Buster Keaton, Indiana Academy Press, in association with British Picture show Establish

- Durgnat, Raymond (1970), "Cocky-Assist with a Smile" from The Crazy Mirror: Hollywood One-act and the American Prototype, Dell

- Edmonds, Andy (1992), Frame-Up!: The Shocking Scandal That Destroyed Hollywood's Biggest Comedy Star Roscoe "Fatty" Arbuckle, Avon Books

- Everson, William Thousand. (1978), American Silent Moving-picture show, Oxford Academy Printing

- Gilliatt, Penelope (1973), "Buster Keaton" from Unholy Fools: Wits, Comics, Disturbers of the Peace, Viking

- Horton, Andrew (1997), Buster Keaton's Sherlock Jr. Cambridge University Press

- Keaton, Buster (with Charles Samuels) (1960), My Wonderful Earth of Slapstick, Doubleday

- Keaton, Buster (2007), Buster Keaton: Interviews (Conversations with Filmmakers Serial), University Press of Mississippi

- Keaton, Eleanor, and Vance, Jeffrey (2001), Buster Keaton Remembered, Harry North. Abrams ISBN 0-8109-4227-5

- Kerr, Walter (1975), The Silent Clowns, Alfred A. Knopf, (1990) Da Capo Press ISBN 0-394-46907-0

- Kline, Jim (1993), The Complete Films of Buster Keaton, Ballad Pub. Group

- Knopf, Robert (1999), The Theater and Cinema of Buster Keaton, Princeton University Press ISBN 0-691-00442-0

- Lahue, Kalton C. (1966), Globe of Laughter: The Motion Motion picture One-act Short, 1910–1930, Academy of Oklahoma Printing

- Lebel, Jean-Patrick (1967), Buster Keaton, A.S. Barnes

- Maltin, Leonard (1978), The Not bad Film Comedians, Crown Books

- Maltin, Leonard (revised 1983), Selected Curt Subjects (offset published every bit The Great Film Shorts, 1972, Crown Books), Da Capo Press

- Mast, Gerald (1973, 2nd ed. 1979), The Comic Listen: Comedy and the Movies, University of Chicago Press

- McCaffrey, Donald Due west. (1968), 4 Corking Comedians: Chaplin, Lloyd, Keaton, Langdon A.Due south. Barnes

- McPherson, Edward (2005), Buster Keaton: Tempest in a Flat Hat Newmarket Printing ISBN i-55704-665-4

- Meade, Marion (1995), Buster Keaton: Cut to the Chase, HarperCollins

- Mitchell, Glenn (2003), A–Z of Silent Film Comedy, B.T. Batsford Ltd.

- Moews, Daniel (1977), Keaton: The Silent Features Close Up University of California Press

- Neibaur, James L. and Terri Niemi (2013), Buster Keaton's Silent Shorts, Scarecrow Printing

- Neibaur, James L. (2010), The Fall of Buster Keaton: His Films for MGM, Educational Pictures, and Columbia, Scarecrow Press

- Neibaur, James L. (2006), Arbuckle and Keaton: Their 14 Film Collaborations, McFarland & Co.

- Oderman, Stuart (2005), Roscoe "Fat" Arbuckle: A Biography of the Silent Picture Comedian, McFarland & Co.

- Oldham, Gabriella (1996), Keaton'due south Silent Shorts: Beyond the Laughter, Southern Illinois University Press

- Rapf, Joanna Eastward. and Green, Gary L. (1995), Buster Keaton: A Bio-Bibliography, Greenwood Printing

- Robinson, David (1969), The Great Funnies: A History of Moving picture Comedy. Eastward.P. Dutton.

- Scott, Oliver Lindsey (1995), Buster Keaton: The Picayune Fe Man. Buster Books.

- Smith, Imogen Sara (2008), Buster Keaton: The Persistence of ComedyGambit Publishing ISBN 978-0-9675917-4-2

- Staveacre, Tony (1987), Slapstick!: The Illustrated Story Angus & Robertson Publishers

- Stevens, Dana (2022). Camera Man: Buster Keaton, the Dawn of Cinema and the Invention of the 20th Century. New York: Atria Books. ISBN9781501134197. OCLC 1285369307.

- Yallop, David (1976), The Day the Laughter Stopped: The Truthful Story of Fatty Arbuckle. St. Martin's Press.

External links [edit]

- Buster Keaton at IMDb

- Buster Keaton at the TCM Movie Database

- Buster Keaton at Rotten Tomatoes

- The International Buster Keaton Guild

- Buster Keaton Museum

- Buster Keaton and the Muskegon Connexion

- Buster Keaton in Five Easy Clips

- Buster Keaton Photograph Galleries (includes rare images of BK smiling and laughing)

- Buster Keaton as a child performer (Univ. of Washington/Sayre collection)

- Buster Keaton'south Silent Shorts (1920–1923) by James L. Neibaur and Terri Niemi

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Buster_Keaton

Post a Comment for "1940 Movie in Which a Millionaire Fall in Love With One of Three Sisters and His Family Disapproved"